Montlake Memories: The 1940s

Husky Stadium Centennial Celebration

Jeff Bechthold

10/19/2020

With 2020 marking the 100th anniversary of the first football game at what is now called Alaska Airlines Field at Husky Stadium, GoHuskies.com is marking the milestone with a decade-by-decade look back at some of the big events that have taken place –football games and otherwise – at the Greatest Setting in College Football.

Nov. 16, 1940 – Washington 22, USC 0

Other than a trip to the Rose Bowl following the truncated 1943 season – Washington played USC in an all-West Coast version of the Granddaddy of Them All that year thanks to wartime travel restrictions – the 1940s do not represent a particularly successful decade on the gridiron for the Huskies, but the prosperity of the late '30s did bleed into the 1940 season.

In 1940, still the pre-War era for the United States, the Huskies finished 7-2 under coach Jimmy Phelan. Washington lost the season opener at powerful Minnesota (the consensus national champion of 1940) and took a loss at Stanford (which finished 10-0, earning a national title in a few polls) in the sixth game of the season.

In the seventh game of the nine-game season, Washington still had a chance at the conference title and a Rose Bowl berth, depending on Stanford's results over the final weeks, when coach Howard Jones brought his USC squad to Seattle for a Nov. 16 matchup with Washington, led by (among others) Ray Frankowksi, Rudy Mucha and Jay McDowell, who all earned All-America that year.

To be fair, USC's 1940 squad was not one of its best, as they Trojans went on to finish 3-4-2, but they had won a share of the national title in 1939, as well as in six of the last 12 seasons under Jones. Washington had give the Trojans fits in recent seasons, however, having won five in a row vs. the Trojans before a two-point loss in '39.

Nonetheless, the Huskies were favored to win their homecoming game. And they did, by a score of 14-0, with Jack Stackpool scoring both UW touchdowns.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer's Clarence Dirks wrote this in the following morning's paper, in a style of writing unfamiliar to today's press:

"Jack Stackpool's temperature was considerably above normal yesterday. As a result, Washington outmuscled Southern California before 30,000 specators as the Stadium, 14-0.

"The wide-hipped Husky fullback who broke out of the arms of Stanford players a week ago to race 58 yards, uncorked a 78-yard touchdown sprint. In the fourth period as dusk fell over hte huge homecoming crowd and little bonfires of programs and cards glowed in the aisles among student rooters, Stackpool side-stepped 4 yards around a massed Trojan wall to add the other score."

The Husky roster was about as stacked as it could be, given that the varsity included just 38 men.

The following spring, Mucha was the fourth player taken in the first round of the NFL Draft, while teammate Dean McAdams went just four picks later. MacDowell was a third-round pick. In the 1942 draft, five Huskies were drafted, led by Frankowski, a second-round selection.

Most of those Huskies went on to play professionally, though nearly all had their careers delayed or interrupted by first serving in the military during World War II before returning in time for the 1945 NFL season.

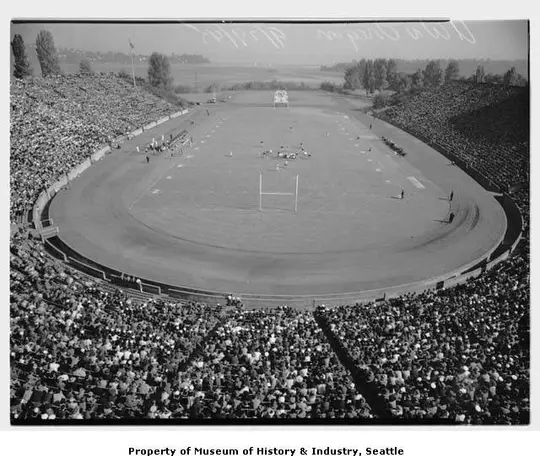

June 13, 1943 – Husky Stadium Under Siege

On the front page of the Sunday, June 13, 1943, edition of the Seattle Sunday Times is a cartoon graphic depicting a fiery explosion with the words "Seattle Will Be Bombed Tonight" written in the center.

The story that followed began:

"Blasts will rend the air as buildings topple. Sirens will scream, their piercing howls almost drowned out by the roar of dive-bombing 'enemy' planes. Anti-aircraft guns will chatter steady defiance of the raiders. Ten thousand volunteers, members of the Civilian Protection Division of the Seattle War Commission, will spring to their posts as flames rage.

"Meanwhile, Mr. and Mrs. Seattle will have grandstand seats at the big show, their first opportunity to learn what to expect should the city be bombed."

It seemed an almost flippant headline and story, given that the same front page included headlines referencing battles in Sicily and Tunisia, bombing in Europe and Asia, and the presumed loss of two U.S. submarines, with 120 men aboard.

That aside, the story laid out some of the details of Seattle's Civil Defense Demonstration Day, which was set for 6:00 p.m. that night at the University of Washington Stadium. The evening, free to all attendees, and under the direction of Col. Charles Albert and Seattle Mayor William Devin, featured a demonstration of both military and civilian might, with police, firefighters and civil defense units joining members of the U.S. military.

The most spectacular portion of the demonstration featured mock air raids, with planes flying overhead, anti-aircraft fire and real (but coordinated) explosions and fires.

The following day's Times reported that 35,000 spectators attended, alongside 4,800 civilian defense volunteers. The Times stated that it was "believed to be the first of its kind on a comparable scale in the nation."

No full-scale attacks ever reached the mainland of the United States during World War II, with only a Japanese submarine shelling an antiquated base on the Columbia River and six fatalities in Oregon ascribed to balloon bombs that had taken a three-day trip over the Pacific Ocean before falling.

The stadium returned to its "normal" use that fall, though on a limited basis. Due to the War, no other program in the northwest (including PCC members Idaho and Montana) fielded a varsity team in 1943 or 1944. The 1943 Huskies, under coach Ralph "Pest" Welch and led by All-Coast selections Jack Tracy, Sam Robinson and Bill Ward, played just four games in the regular season – three of them against military teams – winning all four. UW took its only loss to USC in the 1944 Rose Bowl, Jan. 1 in Pasadena.

September 29, 1945 – Washington 20, Oregon 6

When Washington met Oregon in the first game of the 1945 season, it wasn't the two rival teams that made it a milestone game, it was the occasion.

Earlier that same month aboard the USS Missouri, representatives of Imperial Japan had signed papers declaring surrender, marking the official end of World War II. While there was still plenty of turmoil leftover, especially in the war zones spread all over the world, September of 1945 was the beginning of a return to normal – a new normal perhaps – in the United States.

During the war, Washington was the only major college in the Northwest that fielded a varsity football team in 1943 or 1944. Oregon, Oregon State, Washington State, Montana and Idaho – all members of the Pacific Coast Conference – had shut down for those two falls. But with the war over, and so many young men having returned from Europe and Asia, football was back.

"College football with all of its prewar glamour and thrill returns to the University stadium today," Royal Brougham wrote in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Saturday morning, "and the most exacting follower couldn't ask for a more auspicious inaugural than this – Oregon vs. Washington.

"New names dot the lineup programs," Brougham continued, "some of the young men on both teams still wearing the tan of bitter South Pacific campaigns, and the visiting coach, Tex Oliver, has just recently changed from navy blue into civies.

"But war will be just a bad dream to these two traditional rivals when the whistle blows at 1:30 today. In anticipation of a close, hard contest, one of the largest opening day crowds in Washington history will be there for the kickoff."

Washington won the game, 20-6, before a packed house in the stadium. Washington held the Ducks on a pair of goal-line stands early on, and then scored on a 35-yard interception return from 17-year old freshman Norm Sansregret and a short touchdown pass from another 17-year old, Joe Stone, just before the half.

In the third quarter, Stone added a touchdown pass and Oregon scored late in the fourth for its only score.

Along with game coverage, the Sunday Seattle Times included a column from sports editor Sandy McDonald, who noted that Oliver had spent time all over the globe during his war service – "Iceland, Greenland, the Caribbean, South Atlantic, Africa and eventually to many points in the vast Pacific" – went on to write about how both teams' coaches thought the opening of the season had come too early, and that the PCC should have delayed the re-start of college football on the West Coast.

"Tex feels that with the young and the inexperienced players available for the various teams this year the Northern Division of the conference should have allowed for a longer preseason practice before throwing the kids into action," McDonald wrote. "And Ralph Welch, Washington's head man, agrees with Oliver.

" 'The conference games have been scheduled far too early this fall,' Tex told us Friday. 'At Oregon — and I presume the same situation exists at most of the other Northern Division schools — we have two classes of football players this season, the 17-year old freshmen and the 24-25-year old returned war veterans. The armed services have taken virtually everyone in between.' "

Indeed, the UW roster in that season's game program showed that the Husky varsity included a dozen 17-year olds, and also several players denoted as "Navy trainees."

McDonald wrapped up Oliver's quote: " 'The youngsters are green, the veterans are fat. Somebody's going to get hurt.' "

Washington, which played no non-conference games in that 1945 season, finished the year with six wins and three losses, playing two games each vs. Oregon, Oregon State and Washington State (and one each vs. Cal, USC and Idaho).

Sansregret and Stone each played only that one season at the UW, as their academic careers were no doubt affected by the tumultuous, early post-war years. Sansregret, who joined the Army after the 1945 season, went on to play football alongside eventual 1948 Heisman Trophy winner Doak Walker for a military team in San Antonio, Texas, before returning home to Bellingham, where he attended and played football at Western Washington University.