Montlake Memories: The 1930s

Husky Stadium Centennial Celebration

Jeff Bechthold

10/19/2020

With 2020 marking the 100th anniversary of the first football game at what is now called Alaska Airlines Field at Husky Stadium, GoHuskies.com is marking the milestone with a decade-by-decade look back at some of the big events that have taken place –football games and otherwise – at the Greatest Setting in College Football.

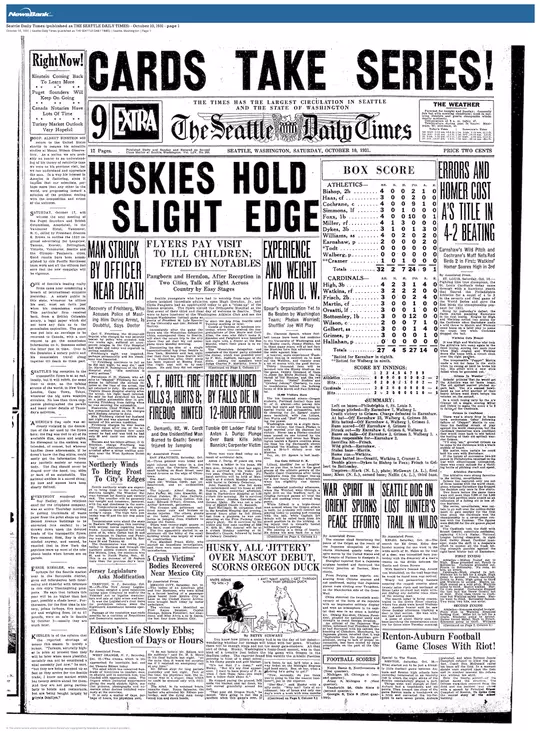

October 10, 1931 – Pangborn and Herndon Attend UW-Oregon Game

Other than perhaps Amelia Earhart, no aviator ever came close to achieving the level of lasting fame that Charles Lindbergh did, when he flew from New York to Paris in 1927. But, even after Lindbergh's famous feat, other flyers continued to conquer new challenges.

Two such fliers were Clyde "Upside-Down" Pangborn and Hugh Herndon Jr., who became the first men ever to traverse the Pacific Ocean non-stop, in October of 1931. While their memory may be familiar now only to aviation enthusiasts, they were household names in late '31. And like Lucky Lindy, they visited Husky Stadium shortly after they completed their historic feat.

Pangborn, who was born in Bridgeport, Wash., near Lake Chelan, had gained a reputation as a top barnstorming stunt pilot (earning his nickname), after serving as a flight instructor during World War I. Herndon was the son of Standard Oil heiress Alice Boardman, who had helped finance the pair's attempt to break the world record for circumnavigation, which ended unsuccessfully in eastern Russia, from where they continued on to Japan.

After having been arrested in Japan for landing their plane without permission and on suspicion of spying (Japan was engaged in a long period of aggression with China), the pair were tried, convicted and spent seven weeks on house arrest before earning permission to attempt the transpacific flight, which many had attempted (or at least planned for), but none had accomplished. Among others, a Japanese newspaper and the City of Seattle had offered prize money to the first to complete the flight, with all sorts of specific requirements and caveats. Seattle's prize, originally $25,000, had grown to more than $29,000, thanks to the accrual of interest since it had first been offered.

On Oct. 4, they took off from a beach in Misawa, Japan, in their plane, the Miss Veedol. After jettisoning their landing gear after takeoff to shed weight and decrease drag, they managed to make it to Alaska and down the length of British Columbia before "belly landing" on Monday, Oct. 5, in what is now East Wenatchee, Wash., not too far from Pangborn's home town. The flight took 41 hours and 13 minutes.

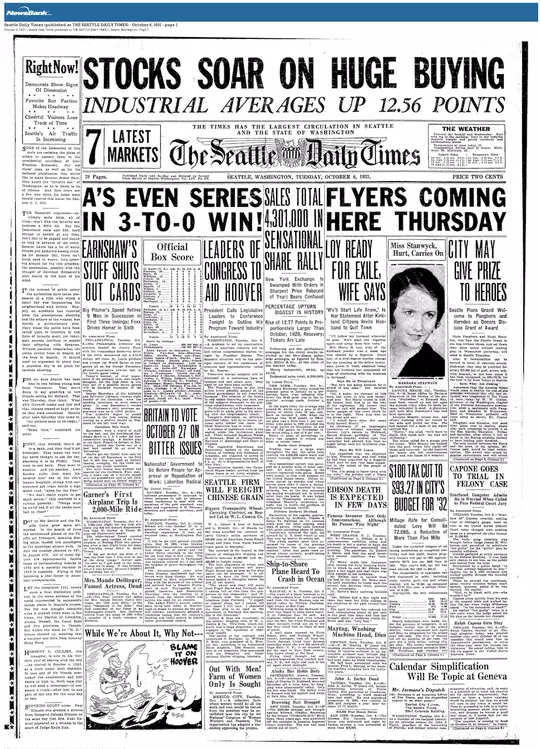

In Tuesday's Seattle Times, the headlines announced, "Flyers Coming Here Thursday," followed by "City May Give Prize To Heroes." It was not yet clear if all legal issues regarding the prize had been settled. The Times' story included the following paragraphs:

"Clyde Pangborn and Hugh Herndon, who flew the Pacific Ocean in one hop without shoes, and set down their plane safely without landing gear in Wenatchee yesterday, will come to Seattle Thursday."

"Assurance that the nonstop flyers would come to Seattle for one of the greatest welcomes this city has extended was telephoned to the Times at noon today by W.W. Connor, governor of the Washington chapter of the National Aeronautics Association ... Half of Wenatchee probably will come along as escort."

"Pangborn and Herndon will send their plane over to Seattle, where they have consented to exhibit it at the Bon Marche [department store] Thursday, Friday and Saturday, after which it will be taken to the Boeing airplane factory to have landing gear installed."

The two fliers did indeed arrive in Seattle that Thursday, after which they were paraded and whisked around town to a variety of celebrations, along with a visit to Seattle's Orthopedic Hospital (now Seattle Children's), which was then located atop Queen Anne Hill.

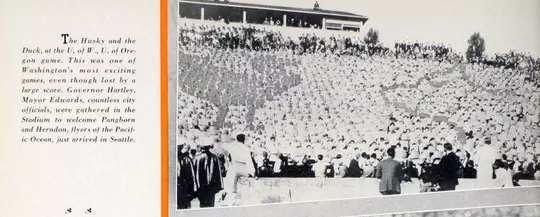

The final "official" event of their stay in Seattle was attending the Washington-Oregon football game that Saturday at Husky Stadium, which was memorialized in the 1932 Tyee yearbook.

The pair of men did not, in the end, earn the Seattle prize money (which was contingent on the flight originating in Seattle), but were awarded $50,000 by the Japanese newspaper.

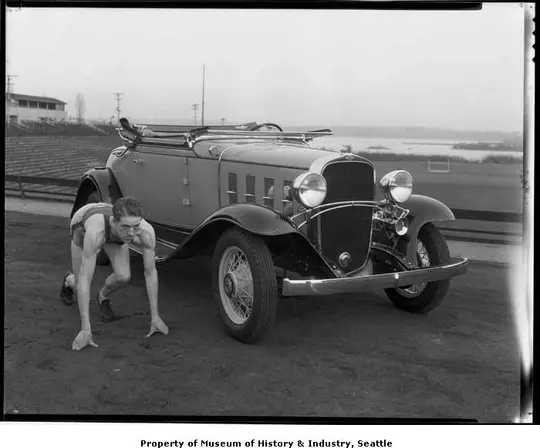

May 6, 1932 – UW-WSC Dual Track Meet: Huskies 68, Cougars 63

One wonders if the newspaper headlines would have spent more ink on this historic track meet the next morning had not the President of France, Paul Dormer, not been killed by an assassin's bullet in Paris the very same day.

Not surprisingly, it was Dormer's death that dominated the front pages of that Saturday's papers, but the Huskies' track and field victory over Washington State was also top news in Seattle, primarily because the annual meet, held in even-numbered years at Husky Stadium, came down to the last leg of the final event of the day, the mile relay.

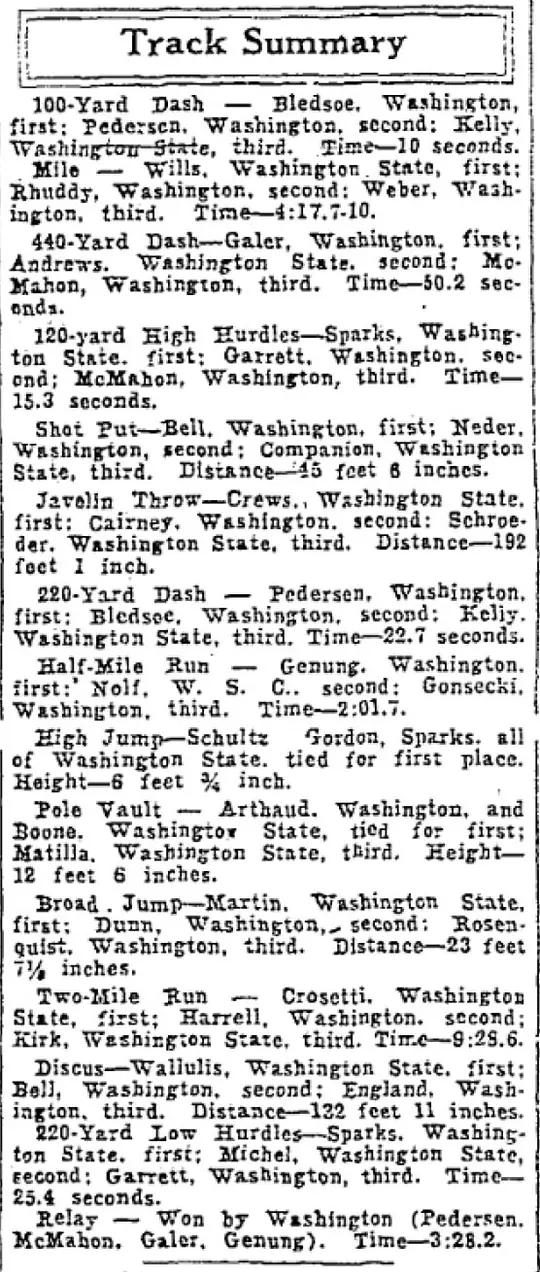

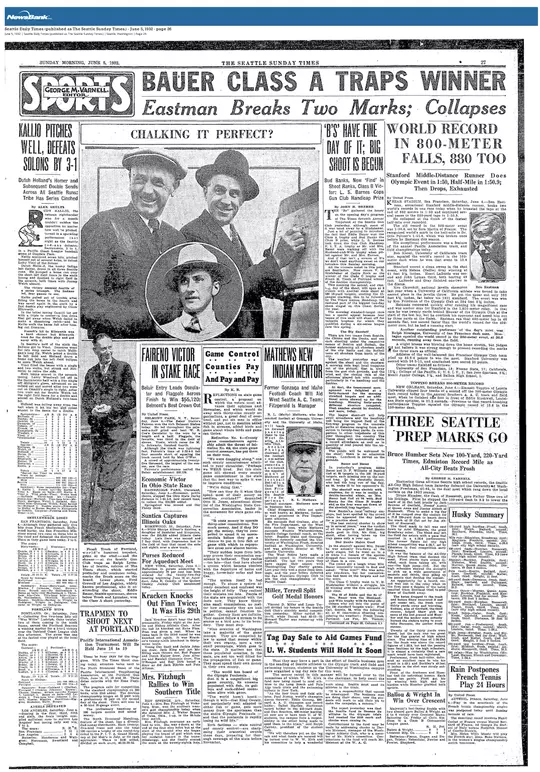

The meet was tied at 63 points apiece with only the relay left to run. With five points given to the victorious foursome, it was winner take all. Washington's captain and anchorman Eddie Genung won the race for the home team, narrowly beating WSC's Ken Wills in the anchor leg.

Genung, who had earlier the same meet won the half mile, led a relay team that included Ross Pedersen, Paul McMahon and Fred Galer, who passed the baton to Genung, trailing the Cougars' anchor by about eight feet.

Wills (who'd won the mile run earlier in the meet) led most of the final leg, but Genung, who had won the 1929 NCAA championship in the half mile and went on to finish fourth in the 800 meters at the 1932 Olympics, moved in front with about 80 yards to go, and won by about six feet.

Legendary Seattle Post-Intelligencer sportswriter Royal Brougham used the first portion of his column the Sunday after the meet to laud Genung:

"Chin out, knees chugging up and down like pistons, teeth tightly set – that's chesty Eddie Genung breezing to the tape in the 880," Brougham wrote. "With a flair for the spectacular, the diminutive national champion loves to come from behind to win. He has deliberately permitted an opponent to pass him, so that he could come flashing home with a hair-raising sprint.

"Genung loafed along in his half-mile against W.S.C. Friday," Brougham concluded. 'But when the winning of the meet depended upon his spindle shanks in the relay, he started packing the mail, overcame a four-yard lead and beat a crack quartermiler from Cougarville to win the event and the meet."

Wills, incidentally, an All-PCC basketball player for the Cougars who narrowly missed making the 1932 U.S. Olympic track team himself, ended up as a legendary high school basketball and track coach at Bremerton High. In late Dec., 1999, the Kitsap Sun newspaper named him Kitsap County's coach of the century.

Genung, who was also a three-time AAU national champion in the 880, was inducted into the Husky Hall of Fame in 1982, four years prior to his death.

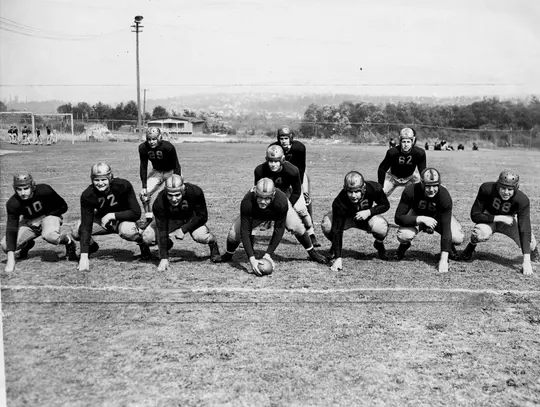

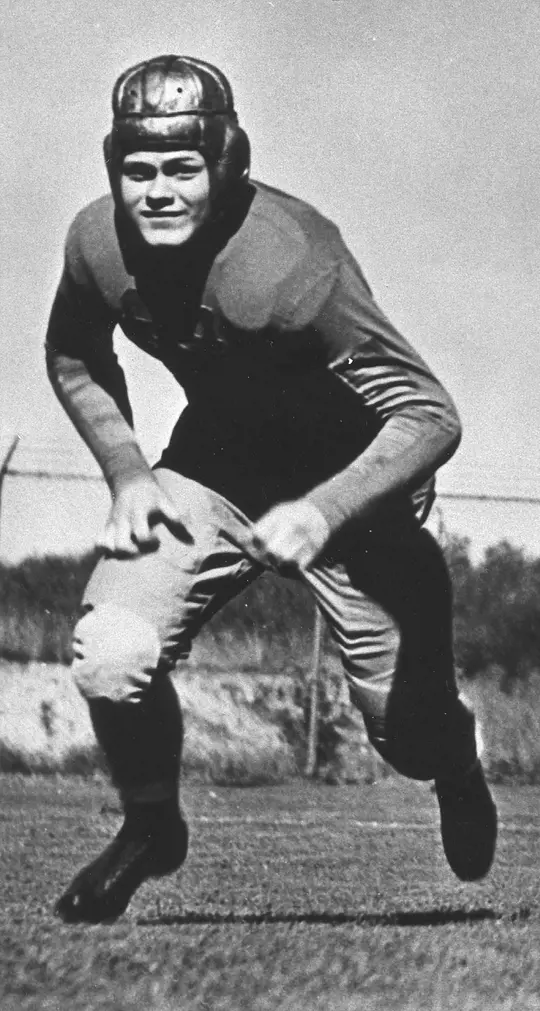

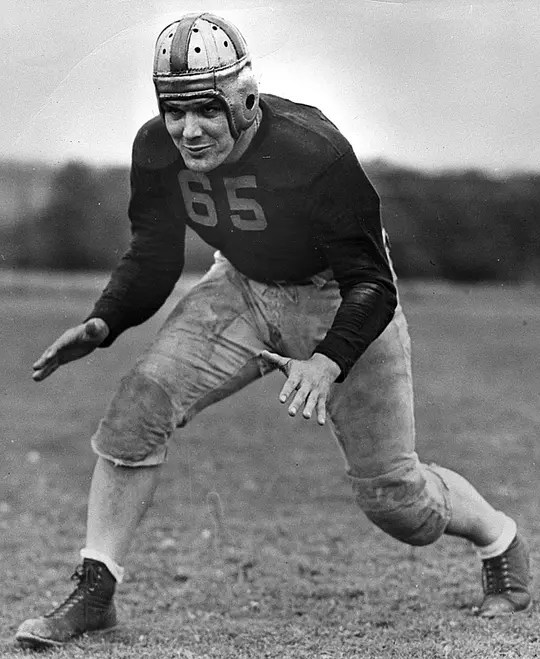

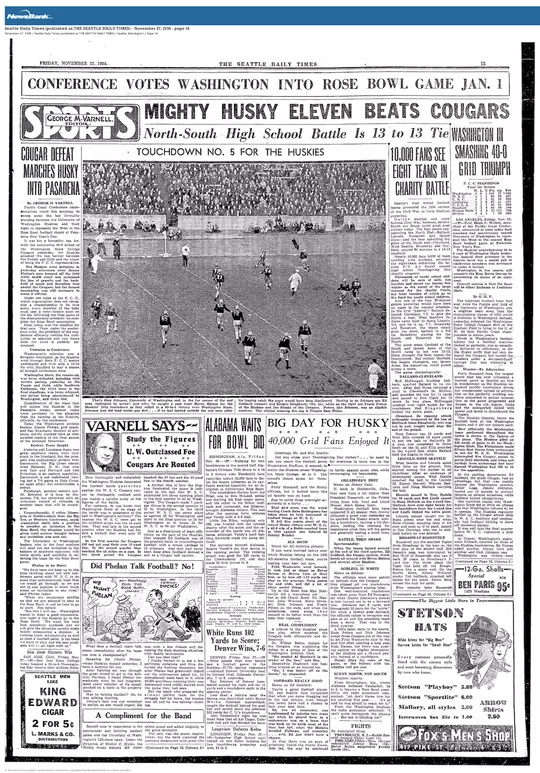

November 26, 1936 - Washington 40, Washington State 0

Coach James Phelan came to the UW following the 1929 season, when his predecessor Enoch Bagshaw had not had his contract renewed. Phelan, who grew up in Portland, played quarterback at Notre Dame from 1915-17 and had already served as head coach at Missouri and Purdue.

The first several years of his UW tenure were marked by winning seasons, but nothing particularly spectacular. However, in 1934, his Huskies finished with a 6-1-1 record and beat USC for the first of five straight victories over the Trojans. In 1936, the Phelan era reached its peak, as the Huskies won the Pacific Coast Conference and earned a trip to the 1937 Rose Bowl.

The biggest win of that season came vs. Washington State, on Thanksgiving Day, at Husky Stadium. The game pitted the top two teams in the Pacific Coast Conference standings against one another. Both teams entered the game with 6-1-1 overall records. The Huskies were 6-0-1 in PCC play (the only blemish a 14-14 tie at Stanford), while WSC had a 0-0 tie at USC and a loss to Oregon State against its six wins. The PCC title and, likely, the Rose Bowl, were on the line. In those days, the conference's Rose Bowl berth was decided by a vote of member schools, not simply awarded to the team with the best record.

Sports editor George M. Varnell previewed the game in that afternoon's Seattle Times:

"All roads led today to the University of Washington stadium, where at 1:30 o'clock this afternoon the University of Washington and Washington State College meet in the ranking football game of the National Turkey Day football schedule."

"Certain it was that all attendance records for football games in Seattle would be broken at the game. The contest was a complete sellout today. That means that 40,000 persons will be jammed into the seats for the kickoff. And the probability was that another thousand fans, unable to secure seats, will stand around the horseshoe to see the great battle."

What was expected to be a close contest was not. Washington dominated throughout, as the 40-0 score would indicate. The Huskies rushed for 299 yards while holding the Cougars to just 15. WSC managed just two first downs, punted nine times, and never once possessed the ball in UW territory.

The Friday Seattle Times coverage led with the following:

"Greetings, Mr. and Mrs. Seattle: Did you enjoy your Thanksgiving Day turkey? . . . no need to ask you about the football game, for everyone in town was in the Washington Stadium, it seemed, to watch the Huskies smear Washington State College, 40 to 0. The crowd's cheers spoke for themselves.

"Forty thousand, said the Husky officials, but it looked more like all Seattle was on hand."

Incidentally, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer had no coverage of Husky football that entire fall, as its writers had been on strike since August 13. They settled with the Hearst Corporation and went back to work on Nov. 30, the Monday after the final game of the regular season.

Phelan, who was fired at the end of the 1941 season just six days after the attack of Pearl Harbor, was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1973 and the Husky Hall of Fame in 1986. He was replaced for the '42 season by his assistant coach, Ralph "Pest" Welch, who had also been let go initially.

Welch, it's worth noting, led the Huskies to the 1944 Rose Bowl, but his six years as head coach were only moderately successful (27-20-3). He is a member of the Purdue Athletics Hall of Fame, thanks to a successful playing career under Phelan.