Montlake Memories: The 1920s

Husky Stadium Centennial Celebration

Jeff Bechthold

10/12/2020

With 2020 marking the 100th anniversary of the first football game at what is now called Alaska Airlines Field at Husky Stadium, GoHuskies.com is marking the milestone with a decade-by-decade look back at some of the big events that have taken place –football games and otherwise – at the Greatest Setting in College Football.

November 27, 1920 – Husky Stadium Opens to the General Public

A broad series of events over the course of 25 years converged to bring about the building of the University of Washington's new stadium, which was christened in the final game of the 1920 season as the Huskies played host to Dartmouth, on Nov. 27, the Saturday after Thanksgiving.

Two and a half decades earlier, in 1895, the UW relocated its campus from downtown Seattle to its present location on the shores of Lake Washington. Years later, prior to World War I, the long-planned construction of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, which would connect Lake Washington to Puget Sound, began, with the Montlake Cut officially opening in 1917.

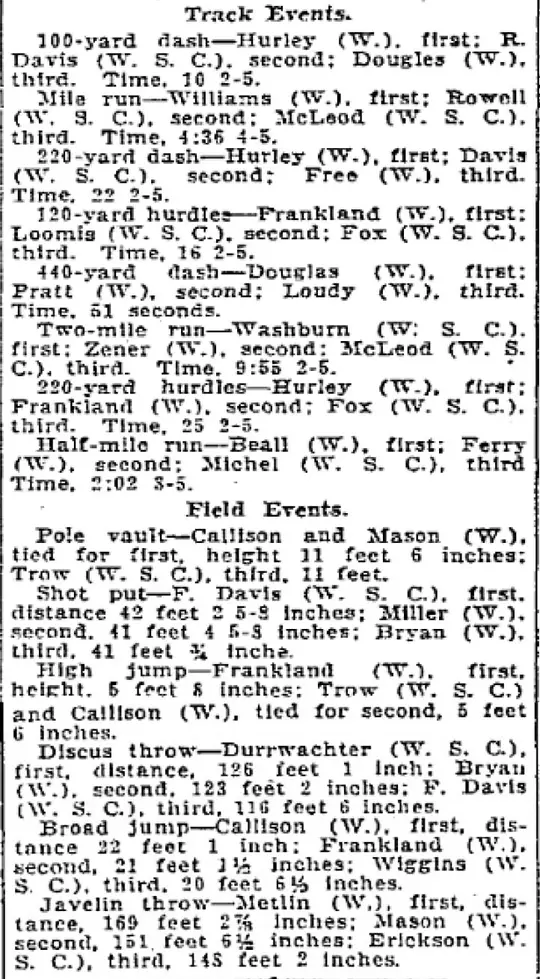

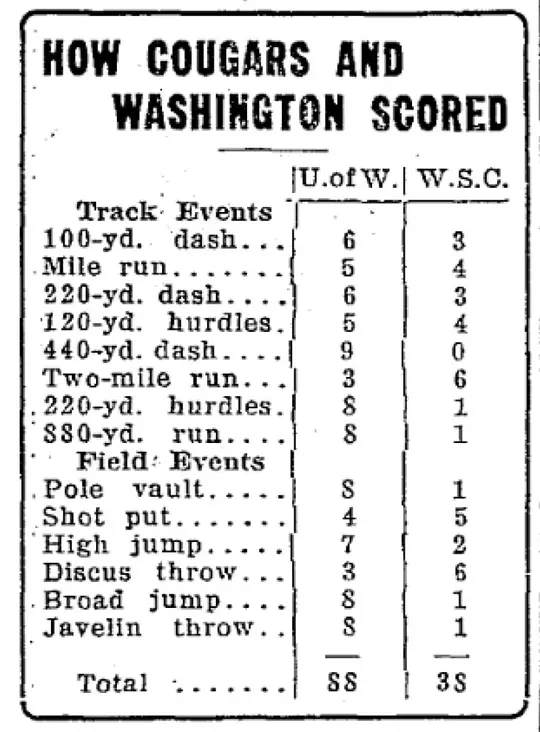

May 13, 1922 – UW Defeats WSC In First Dual Track Meet At Stadium

While Washington's venerable stadium is most closely associated with football, it also served as the home of the UW's track and field program for most of its 100 years.

The annual dual meet between Washington and its in-state rival, Washington State (the school was known as Washington State College (WSC) until 1959) was first held 1901, a UW victory in Seattle.

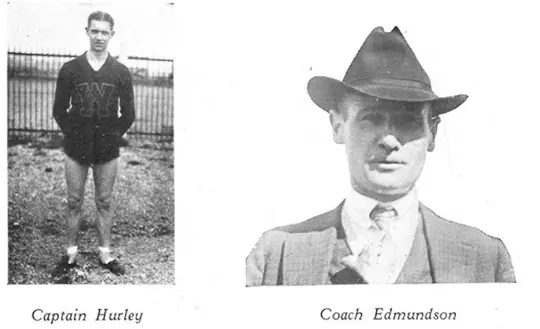

But the first UW-WSU track meet at the new stadium didn't come until May 13, 1922, when the home team, coached by Clarence S. "Hec" Edmundson, posted a resounding 88-38 victory over Fred Bohler's Cougars.

Washington won every event but the shot, discus and two-mile run and were led by Chuck Frankland, who won the high hurdles and the high jump while also taking second in the low hurdles and broad jump.

Team captain Vic Hurley took first in the 100-yard dash, the 200-yard dash and the 220-yard low hurdles.

The meet received good coverage in both the Seattle Daily Times and Post-Intelligencer, with glowing reviews for Edmundson's men. The Times did note, however, "The one big disappointment came when Doc Bohler, in charge of the Washington State team, refused to run the relay race, an event on the card which hundreds of spectators would rather see than all the other races put together. Bohler's excuse was that he had no men capable of winning the event."

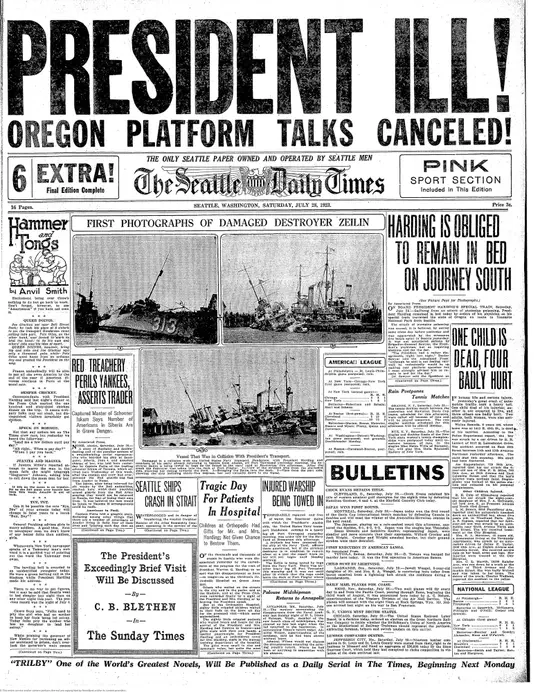

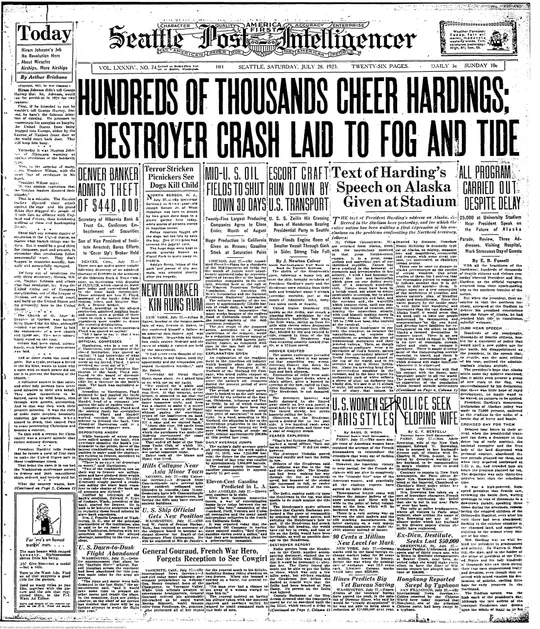

July 27, 1923 – President Harding's Final Public Speech

In the summer of 1923, Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States, embarked on what was planned to be a 40-day tour of the Western U.S. and Alaska. Just the sixth U.S. President ever to visit Seattle while in office (future President Herbert Hoover was in Harding's travel party as Secretary of Commerce), Harding arrived via ship from Alaska at 1:15 p.m. on July 27, for a busy, five-hour stay. His voyage hadn't been without complication as his ship collided with a U.S. destroyer near Port Townsend earlier that morning.

After reviewing the U.S. fleet in the Seattle harbor, he made several appearances around town before his final stop of the day, a speech at what is now Husky Stadium. The speech primarily centered on Alaska, with Harding suggesting that it might soon become a state (Alaska didn't achieve statehood until more than 35 years later, on Jan. 3, 1959).

Harding departed that evening, aboard a train headed south. The next evening's Seattle Times' blaring headline shouted "PRESIDENT ILL!" above the following account from the Associated Press:

"Suffering from an attack of ptomaine poisoning, President Harding remained in bed today by orders of his physician as his special train traversed the state of Oregon en route to Yosemite National Park from Seattle.

"The attack of ptomaine poisoning was caused, it is believed, by eating some crabs day before yesterday and was aggravated by the strenuous five hours spent in Seattle yesterday. It was not considered serious by Brigadier-General Sawyer, the President's physician, but as requiring absolute rest for the day."

Both the diagnosis and prognosis turned out to be incorrect as Harding, who had reportedly begun to recover (a Seattle Times' headline for Aug. 2 was "Harding's Physicians Are More Confident;" another from earlier read "Doctor Sees No Cause For Alarm"), died on the evening of Aug. 2, in his San Francisco hotel room, from what is now believed to be cardiac arrest. His last public appearance had been on the UW gridiron.

Very early the following morning (2:47 a.m. ET), Vice President Calvin Coolidge, who himself had visited Seattle and the UW (but not the stadium) in August of 1922, was sworn in as the nation's 30th President (by his father, a notary public and justice of the peace) at his family home in Vermont, where he was visiting.

It would be 19 years until another sitting President visited Seattle, when Franklin Roosevelt toured the area's military installations and factories in September, 1942.

October 20, 1923 – Washington 22, USC 0

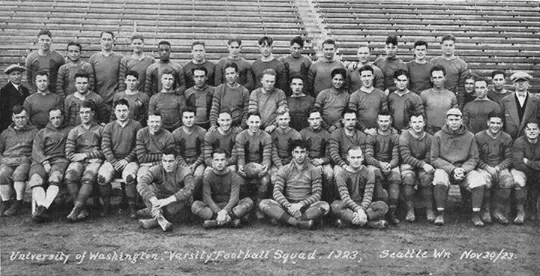

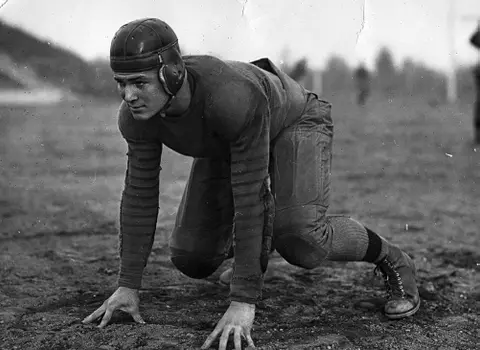

Since the end of the 1920 season, when Enoch Bagshaw was hired to replace Leonard Allison as Washington's football coach, optimism around the program had grown.

Welsh-born Bagshaw, a star player for the Huskies from 1903 to 1907, had fought for the United States in World War I and then taken the helm of the powerful Everett High School football team, which on Jan. 1, 1921, beat East Technical High of Cleveland, Ohio, to win the high school national championship, certainly an extraordinary feat for a school tucked away in the Pacific Northwest.

Several of his Everett players – most notably George Wilson – followed him to the UW, where he relied largely on younger players in his first season, building towards 1923. In the Tyee yearbook's recap of the '21 season, that optimism was clear:

"Washington is looking forward to the 1922 football season with hopes of a winning team. These hopes are not unfounded on fact. The dope points decidedly towards a winning team. The teaching and administrative qualities of Coach Bagshaw are beginning to show themselves in lining up football material of first calibre." The '22 squad finished 6-1-1, losing to Cal and tying Oregon.

The following year, the Tyee included the following under the headline "Watch '23!": "Baggy is beginning to reap the harvest of two years hard work at Washington. His system is beginning to tell ... Football teams are not made in a year, nor in two years, but in three years, results should begin to show. Unless things go very much amiss, Washingtonians may expect this year's team to do things on a large scale for Washington."

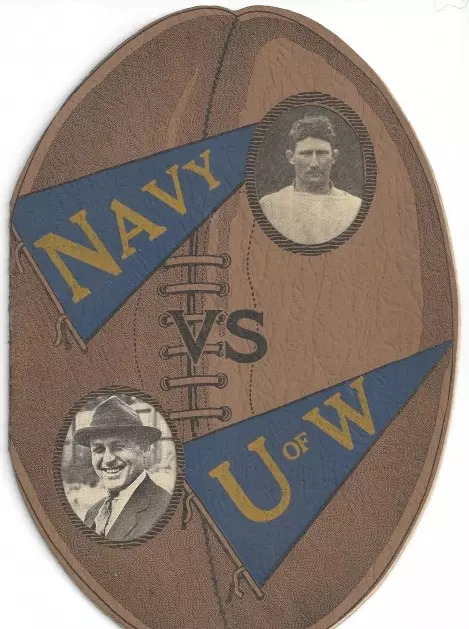

All of that work bore fruit when the Huskies (who had only earlier that year taken on the new mascot name) finished the regular season 10-1 and earned the UW's first-ever trip to the Rose Bowl, where the Huskies played to a 14-14 tie with Navy.

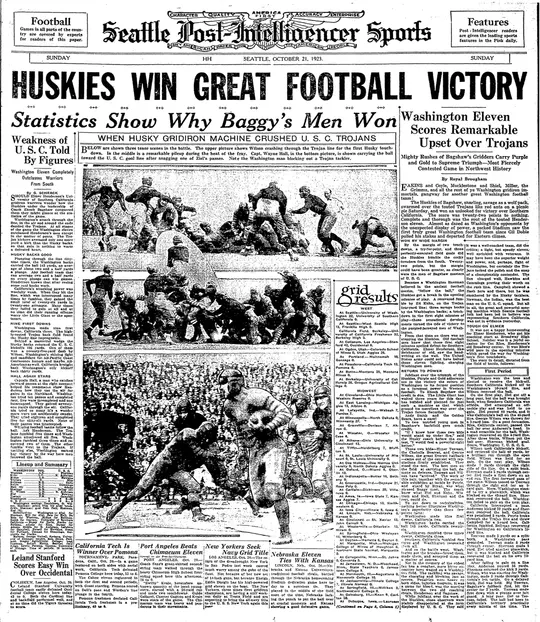

Since the stadium had opened at the end of the 1920 season, the UW had really not managed a "big" victory at the new home. That changed on Oct. 20, 1923, when the Huskies vanquished the mighty Trojans, 22-0, in the most important and impressive of their 10 victories that season.

Washington's win was both dominating and simple as the Huskies scored in each quarter. Wilson and Lester Sherman each scored touchdowns, while Sherman added a conversion and a field goal to build a 16-0 lead at the break. Leonard Ziel added two more field goals in the second half to complete the romp.

To say the news coverage of the win was complimentary would be a major understatement. Here's legendary sportswriter Royal Brougham, evoking great UW players and teams of the past, in the following day's Post-Intelligencer:

"Eakins and Coyle, Mucklestone and Shiel, Miller, the Grimms and all of the rest of ye Washington gridiron immortals, gangway for another great Washington football team!

"The Huskies of Bagshaw, snarling, savage as a wolf pack, swarmed over the touted Trojans like red ants on a picnic pie Saturday, and won an unlooked for victory over Southern California. The score was twenty-two points to nothing. Complete and thorough was the rout of the touted [USC coach Gus] Henderson eleven. Almost as dazed as Washington's opponents by the unexpected display of power, a packed Stadium saw the first truly great Washington football team since Gil Dobie pulled his stakes and departed for Eastern climes."

In the Seattle Times, sportswriter Anvil Smith wrote:

"King Agamemnon of Ancient Greece, after a siege of the city of Troy, brought about the city's fall by sneaking in a wooden horse filled with men. 'King' Bagshaw's troops yesterday sacked the Trojans from the University of Southern California, but they didn't need a wooden horse to do it.

"The ancients used to offer sacrifices before going into battle and priests in flowing robes foretold the future. At the Stadium, the Sophomore-Freshmen 'tie-up' took the place of the sacrifices and the sea gulls flying over the football field were said to be a good omen for Washington."

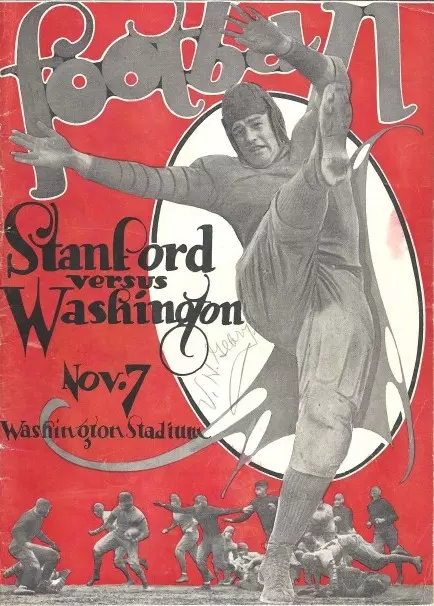

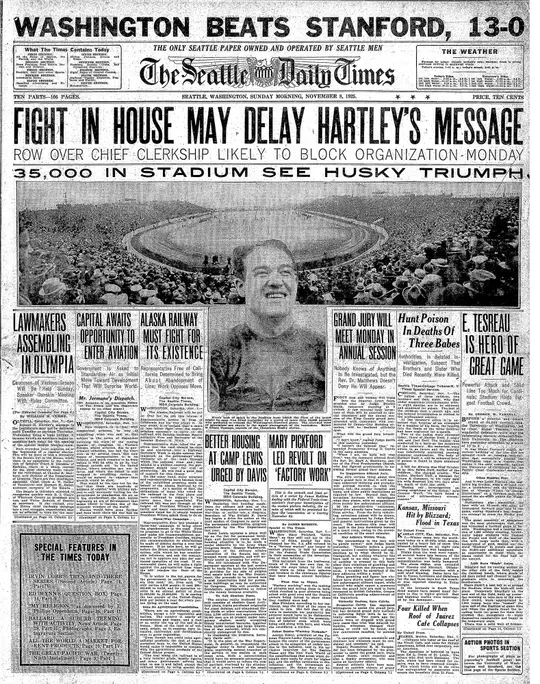

November 7, 1925 – Washington 13, Stanford 0

Another of the first truly "big games" at Husky Stadium (this one certainly came with higher levels of anticipation than the USC game had two years prior) came in its fifth full season of operation, when legendary coach Pop Warner brought his Stanford squad to Seattle for a Homecoming game.

Stanford came to Montlake with a 5-1 record, highlighted by a 13-9 win over USC in front of 70,000 fans in the Los Angeles Coliseum three weeks prior. The Huskies' only blemish on a 6-0-1 record (four wins by shutout) was a 6-6 tie at Nebraska. UW had opened the season with a 108-0 victory over Willamette.

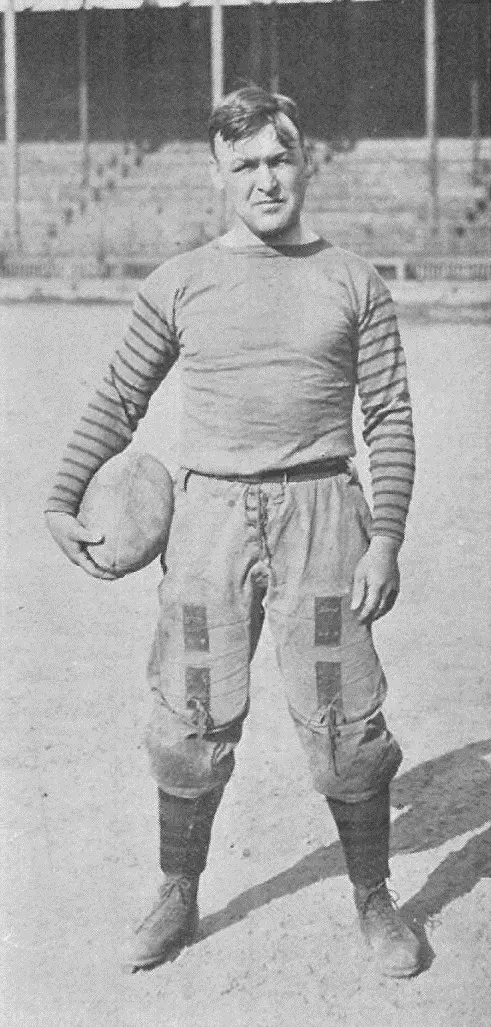

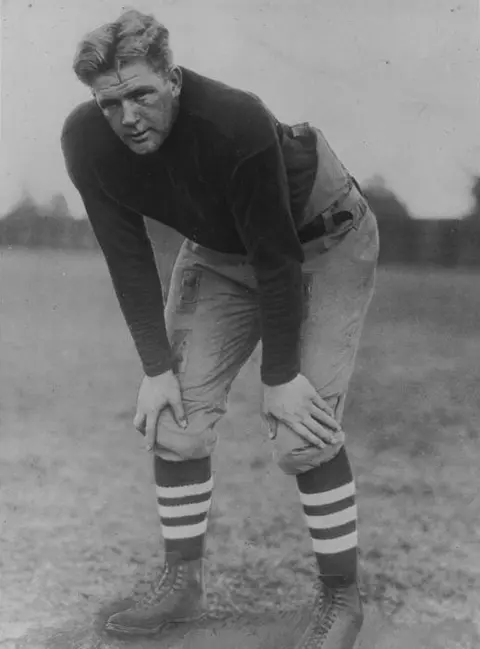

The game was billed as a matchup between Stanford great Ernie Nevers, perhaps the greatest player in his school's history to that point, vs. George Wilson, who held the very same distinction at UW. The fact that it was Homecoming only added to the excitement.

The day of the game, the Seattle Times heralded "35,000 Gather For Husky-Cardinal Game" across the top of page one, with the sub-headline, "Collegiate Spirit Holds Sway Over Entire City."

Washington, behind Wilson, prevailed, but it was Elmer Tesreau – the tough team captain from Chehalis who had played most of the 1924 Rose Bowl game with a broken leg – who out-shined them all. George Varnell wrote in the Times the following day, "It was Elmer Tesreau's crafty, ferocious bucking of the line and his splendid work at running interference that successfully steered the Washington team to a victory that makes it the only contender against the University of California for the Pacific Coast Conference championship."

The UW scored its points on a 60-yard run from Elmer's brother, Louis, and a 26-yard pass from Wilson to George Guttormsen, who had both played under Bagshaw at Everett High School.

The legend that has endured from that game largely concerns Wilson and Tesreau shutting down Nevers. And the Seattle Times' confirmed that the following day with columnist Cliff Harrison heaping praise on Tesreau.

"Big Elmer's opponent was Ernie Nevers, the man mountain of the Stanford team," Harrison wrote. "Up and down the Pacific Coast Nevers has gone, strewing football fields with flattened opponents, scoring on every team he ever faced ... But in Seattle on November 7, 1925, Ernie Nevers met a better man, a better team. The Washington line was never riddled. Perhaps he'd slice offtackle for a five-yard gain here, or a three-yard gain there. In all he gained 39 yards in nineteen attempts. Tesreau gained 41 in eleven tries.

"But when that powerful countercharge of Tesreau's met him, Nevers was done," Harrison continued. "Twice he was stopped when he had a chance to score a touchdown for his team. And, before the sixty minutes of play was up Ernie Nevers limped from the field, beaten, but in defeat a glorious, heroic figure who went down to defeat with a smile on his face, a hearty handclasp for his opponent and no complaint."

At season's end, Wilson and Nevers were joined in Grantland Rice's All-America backfield by the legendary Red Grange, surely one of the greatest offensive trios ever featured on the same All-America squad.

The gameday scene that Saturday was everything it was cracked up to be. More color from the Seattle Times:

"Temporary bleachers on the east end of the field, built up yesterday morning to take care of the overflow crowd, were appropriated by 2,000 young boys who 'rushed' the open end of the Stadium at game time and when the guards found the invading force too great for them they allowed the youngsters to make themselves comfortable and happy in the temporary seats."

The Times also reported this unusual ceremony: "It wasn't merely a day of football triumph for the University of Washington, for at half-time a fire was built in the middle of the field and fifty-two coeds wearing the academic cap and gown marched out onto the field and, as they passed the flames, dropped $52,000 worth of Stadium bonds into the fire to bring the University just that much closer to full ownership of the athletic field."

Washington beat California, 7-0, the following week before handling Puget Sound and Oregon to wrap up the regular season with a 10-0-1 overall record and a perfect 5-0 mark in the PCC. The Huskies notched six shutouts and out-scored opponents 461-39 over the course of the season. Their terrific year granted them their second berth in the Rose Bowl, where they would face coach Wallace Wade, star player (and future Western film star) Johnny Mack Brown and Alabama, in the Crimson Tide's first-ever bowl appearance.

Alabama won that game, 20-19, thanks in large part to the fact that Wilson missed the entire third quarter with sore ribs. Bama scored all 20 of its points (20-0) while Wilson was sidelined.

One other note: another star on the UW team that season was tackle Herman Brix, who would go on to win a silver medal in the shotput at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam (Brix broke the Olympic record with his first throw, but was later surpassed by a U.S. teammate John Kuck, who broke the world record to win the gold).

Primarily under the screen name "Bruce Bennett," he went on to a successful acting career that spanned nearly 50 years. A few days prior to the Huskies' taking on Purdue in the 2001 Rose Bowl, Brix paid a visit to a UW practice on the USC campus and spoke to the team about his memories of the 1926 Rose Bowl, 75 years prior. Brix died in 2007 at the age of 100.

September 13, 1927 – Charles Lindbergh's Visit To Seattle

On May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh became the world's most celebrated living person when he touched down at Le Bourget airfield in Paris, having flown from New York in his single-engine airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, marking the first solo, transatlantic flight in history.

Less than four months later, on September 13, he landed the very same Spirit of St. Louis at Sand Point Naval Air Station, a couple miles north of Husky Stadium, part of a lengthy speaking tour that saw him visit all 48 states between July and October.

He traveled by boat to the ASUW Shellhouse and was then driven in to Husky Stadium, where he sat atop the back seat of an open limousine. After a couple of laps around the stadium track, he was introduced to the crowd of 25,000 by Seattle mayor Bertha Knight Landes.

After his speech, which was mainly meant to promote the aviation industry, Lindy headed downtown for a parade, which was followed by a banquet at the Olympic Hotel.

In 2015, 82-year old Beverly Hitt Akers of Bellevue found an 88-year old canister of film from the event and donated it to the UW Library, providing one of the earliest motion-picture glimpses of the stadium.